Most people are aware that websites and online services collect data about them in order to serve them with targeted advertising. They may also know that physical stores use ‘rewards’ programs such as loyalty cards to link purchases and serve consumers with targeted discounts and sale offers.

What many people are not aware of, however, is that there is an entire industry of companies whose business model is based around collecting these fragmented datasets, linking them and analysing them to form a profile of an individual consumer. These companies sell information about consumers to a wide range of actors, from marketers to insurers and political parties. Known variously as data miners, data brokers or information brokers, you may never have heard of these companies – but they’ve almost certainly heard of you.

Let’s give an example of one way this might work: meet Marguerite. Marguerite is an avid Facebook user. Facebook knows that she is 34; that she lives in Melbourne but regularly logs in from Perth; that she recently changed her relationship status from married to single; that she is most likely to click on travel and fine dining ads, and (through off-site tracking) that she spends a lot of time browsing food blogs. She has never posted a picture of a child, but Facebook’s image recognition algorithm knows she frequently posts pictures of a dog.

Facebook is connected to a multitude of data miners and data brokers, but for the purposes of this example let’s zoom in on just one. In July 2015 Facebook announced deals with several major data brokers in Australia, one of which was a company called Quantium. Quantium is 50 percent owned by Woolworths, and has access to the huge trove of data generated by Woolworths Everyday Rewards program. In July 2016 the Australian Privacy Commissioner released privacy assessment reports into both Woolworths and Coles loyalty programs. Privacy Commissioner Timothy Pilgrim observed that whilst both corporations were fulfilling their obligations under Australian law, “[I]t’s important that all Australians understand the bargain we strike with a retailer when we join a loyalty program. There’s no such thing as a free lunch, nor a free flight."

Quantium also has relationships with a large range of other major companies. This includes financial institutions such as NAB, which provides it with millions of anonymised credit and debit cardholders and transactional records; News Corp, which supplies it with details on consumers’ reading habits and interests; and health insurers including Medibank and Bupa.

Through a process known as onboarding, Quantium gathers breadcrumbs of information scattered across these online and offline businesses to build up a personal profile of Marguerite. This is likely to include information stretching from basic details like her gender and birthday to inferred characteristics like estimated income, leisure activities, political views, religion, ethnicity or cultural background, education level, entertainment preferences and dietary and exercise habits. Details of her online activity and past purchases can be analysed to form a picture of her lifestyle, daily routine, finances and physical health to an extraordinary level of detail. All of this highly personal information about Marguerite is now sitting on the servers of a company she doesn’t even know exists.

One infamous example of the use of prediction based on analysis of consumer data was when in 2012 Target used analysis of past purchases to figure out that a teenage girl was pregnant and bombard her with ads for baby items – before even her family knew about the pregnancy. Even more interestingly, Target knows that consumers can find this level of targeting creepy and invasive, and takes steps to disguise its actions.

“With the pregnancy products, though, we learned that some women react badly,” a Target executive told the New York Times_ in 2012, “Then we started mixing in all these ads for things we knew pregnant women would never buy, so the baby ads looked random…we found out that as long as a pregnant woman thinks she hasn’t been spied on, she’ll use the coupons. She just assumes that everyone else on her block got the same mailer for diapers and cribs. As long as we don’t spook her, it works."_

The same methods can be used across a huge range of scenarios, from political campaigning to insurance and financial credit checks. Let’s go back to Marguerite. In one of the simplest examples of how her data might be used, a dog food company might purchase targeted advertising on Facebook. Because Facebook knows Marguerite is likely to be a dog owner, Facebook will pepper her newsfeed with ads for that brand of dog food. Through Marguerite’s Woolworths Rewards Card, Quantium knows that she usually buys a competitor brand of dog food and can monitor to see whether she changes her purchasing behaviour in-store, thereby measuring the effectiveness of the online advertising campaign through her behaviour in the real world. In some senses this could be a positive outcome for everyone. The dog food company and Woolworths sell more of their products, Facebook benefits from the advertising revenue and Marguerite finds out about a product she is interested in buying.

There are, however, a number of points of serious concern. Transparency and informed consent is one major sticking point. Like many consumers, Marguerite did not fully read the Terms of Service and User Agreements when signing up for Facebook, joining Woolworths’ Everyday Rewards program, searching on Google or any of the dozens of other products and services she uses on a daily basis. She does not know exactly who has access to her data or for what purposes, and these companies are in no rush to enlighten her. Even after being identified and successfully led into making a purchase she would not otherwise have made, she may not even know she has been deliberately targeted. When it comes to dog food, that may not seem like such a big deal – but what if it were for something more personal, like a particular brand of medication or, given her recent change of relationship status on Facebook, a divorce lawyer? What if it is used to offer her a higher price on flights to Perth than other users might see, because an algorithm has analysed her data and past behaviour and predicted that she is more likely to pay?

This opens the second major ethical question associated with data brokers, and targeted advertising more generally: when is it morally acceptable to target consumers, and when is it not? Where is the line between advertising toothpaste to someone after they book in online for the dentist, and advertising funeral homes to them after they post about the passing away of a loved one? These are serious and complex questions which are not yet receiving the level of attention they deserve from policy-makers. Currently those decisions are being made by companies with a vested interest in growing their industry.

There are also significant security implications which come with holding so much data about so many people. Data brokers are prime targets for hacking. In October 2015, for example, the successful hack of international data broker Experian exposed the personal information of 15 million US customers, including social security and passport numbers. In other cases, criminals may simply purchase people’s personal data from data brokers just like any other customer – and then use it to commit identity theft.

Most or all of this data is also accessible, via subpoena or other methods, to state authorities. Some consumers may not be concerned with private companies tracking their spending habits, analysing their personal chat logs or monitoring their real-time physical locations, but does that lack of concern extend to when all of that information is accessible to the government?

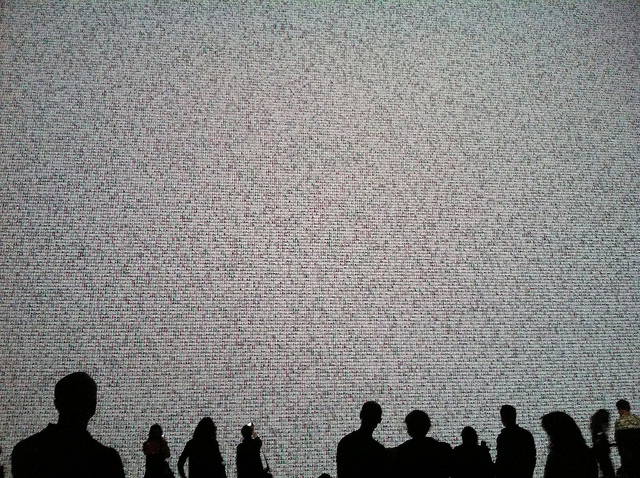

Currently there is a worrying lack of regulation and oversight of the data broker industry. Although data brokers are obliged to comply with Australia’s Privacy Act, the degree to which this really protects the rights and privacy of consumers is highly debatable. Transparency into the inner workings of the industry, including basic details such as who has access to which information, about whom and from what sources, is sorely limited. There is little clarity over how data can, should be or is currently being applied and how the lives of consumers are impacted. This undermines the capacity of consumers to give, or withdraw, their informed consent to corporate data collection. Data brokers should not be allowed to stand behind a one-way mirror, observing whilst themselves remaining unobserved. Appropriate and robust regulation is needed to protect the rights and interests of consumers, particularly those who may be especially vulnerable.

Learn more:

What Facebook Knows About You – ProPublica

When Algorithms Decide What You Pay – ProPublica

Data Brokers: A call for transparency and accountability – US Federal Trade Commission

Immaterial Labour and Data Harvesting – Share Labs

Resources:

Data Selfie – an app which aims to provide a personal perspective on data mining, predictive analytics and our online data identity – including inferred information from our consumption.

Facebook Tool for Google Chrome – a browser extension for Chrome which allows you to see what Facebook says it knows about you.

Lightbeam for Firefox – a browser extension for Firefox that displays third party tracking cookies placed on your computer by websites you visit.