In the 20 years of the “war on terror” Australia has led from the front in expanding powers for law enforcement and ramping up surveillance at the expense of public rights and freedoms.

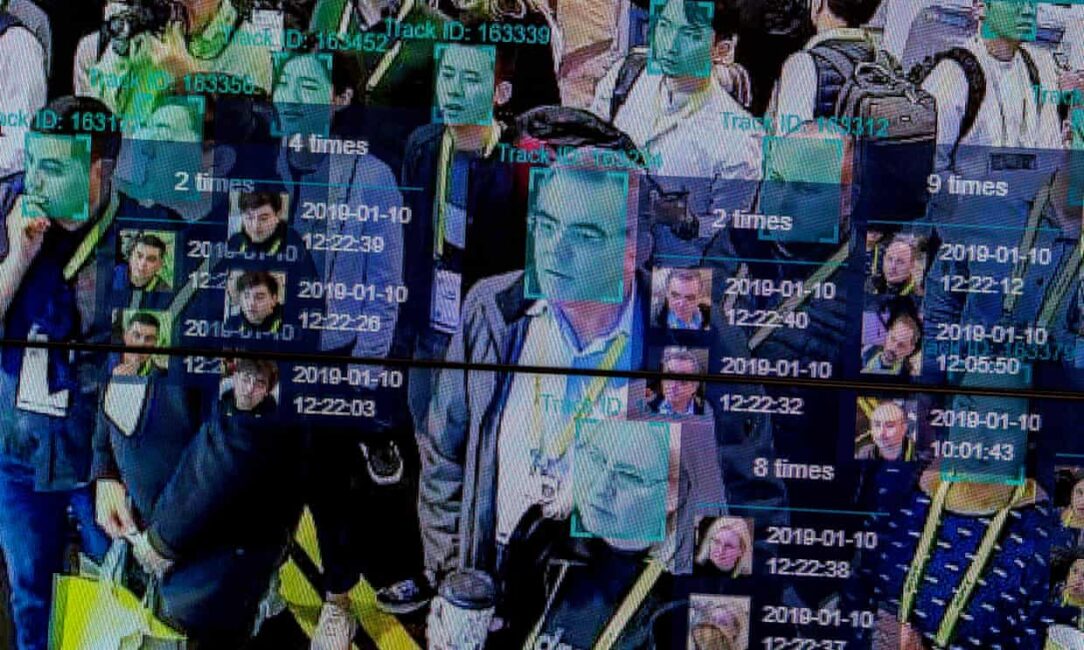

Among the seemingly endless barrage of national security legislation and surveillance that creeps into every aspect of our personal lives, more and more of our public spaces have been smothered by surveillance cameras and facial recognition technology. Corporations large and small, towns and cities, federal and state government departments and agencies have deployed these systems, snooping on us all wherever we go without any of us getting a say. State and federal law enforcement officers are accessing these technologies without any oversight.

As anti-police protests spread around the world, tools and processes that exacerbate racist bias – and the wasteful spending and abuses of power that comes with it –within law enforcement and judicial systems have fallen under renewed scrutiny. Once again, Australia is lagging behind the debate.

Numerous investigations have shown that facial recognition surveillance technology simply does not do what it is supposed to do and is frequently misused by the many agencies that access it. We’re told it’s for community safety yet it frequently reports false positives about vulnerable people in our community, most particularly people of colour.

In two recent cases, facial recognition surveillance led to false accusation and imprisonment in the United States. A surveillance mechanism that sees Black people as indistinguishable, inevitably leading to false arrests, presents a fundamentally different risk to these communities than it does to white people. This is not just an American problem. An Aboriginal person understandably responding with surprise and anger at wrongful arrest will quickly be in real danger.

Some of the most powerful technology companies in the world have recognised the damage facial recognition surveillance is doing. Google, Microsoft and IBM have withdrawn their systems from sale or ceased working on the technology altogether. Even Amazon has placed a moratorium on the sale of its “rekognition” tool to police forces. These companies know the risks and limitations better than anyone and have become vocal detractors.

The tech giants have joined – largely as a response to the seismic shift in public sentiment and the PR issues that come with it – a chorus of social justice and human rights groups calling on governments to ban the use of facial recognition surveillance technology. Additionally, there is agreement on the need to establish regulations and safeguards to protect people’s privacy, guard against misuse of the technology and ensure that any future technologies do not further entrench systemic injustice.

Members of US Congress and some states have supported the initiatives but it is city governments that have led the way; several have blocked the use of the technology in their jurisdictions. Even the tech industry hotspot San Francisco has banned facial recognition surveillance. The City of Sydney became the first in Australia to commit to the UN Cities for Digital Rights initiative, and councillors in others are advocating for their local governments to follow.

At the federal level, there are virtually no safeguards or limits on this technology, and no accountability. This is why senior officials from the Australian federal police can declare that they have not accessed Clearview AI, then have to correct the record later to reflect the fact that several officers have in fact used it. That there was no protocol in place to prevent individual officers using untested technology was a horrifying revelation. Use of the technology needs to be banned, and safeguards and accountability mechanisms within agencies and across governments need to catch up.

The joint investigation into the use of Clearview AI is welcome but needs to be watched carefully because it could be an attempt to generate a social licence for the use of the tool by law enforcement. Scrutiny of the notoriously opaque platform is a useful step but there is so much more to do.

Scaremongering from surveillance and law enforcement agencies is ramping up in response to the Covid-19 crisis. The blueleaks documents in the US revealed that Homeland Security is alarmed that widespread mask wearing will thwart facial recognition systems, seemingly oblivious to the existing shortcomings of the systems. There are growing calls within those agencies to legislate to ban facial coverings at protests. Less scrupulous vendors are seizing the opportunity to claim that “new and improved” facial recognition systems can identify people wearing masks.

In Australia a push to expand the role of the Australian Signals Directorate to spy on Australians from Peter Dutton came under the guise of a call for “public debate” about domestic surveillance. In June Home Affairs launched the Enterprise Biometric Identification Services system without any such debate. This is a new tool allowing it to match the facial images and fingerprints of anyone wanting to enter the country. Another attempt to implement the national biometric matching system, “The Capability”, can’t be far behind.

Legislation for that system was scrutinised by the bipartisan (and normally compliant) parliamentary joint committee on intelligence and security. Its report said the bill was critically short of detail and that a “significant amount of redrafting and not simply amending” was required to redesign the legislation to ensure privacy, transparency and robust safeguards. The committee report also stated that the system needs to be subject to parliamentary oversight.

That is true of the entire apparatus. It is imperative that our governments follow the lead of cities here and abroad to suspend the use of facial recognition surveillance, and commit to developing a regulatory and legal framework that protects people and privacy, and prevents abuse. Federal and state governments must engage with civil society, industry, other experts and the public in a transparent process to put these constraints in place before this technology gets beyond our capacity to control it.

This piece was originally published in The Guardian on 7 August 2020.